Experimenter effects:

If you WANT to find bugs, you are more likely to find bugs / if you adopt a nicey-nicey attitude and just want to help the programmers demonstrate that their program works, you’re going to miss a lot of bugs. It’s not just that you will not report them. You’ll just not see them.Cem Kaner, BBST® Bug Advocacy, Lecture 6, slide 168.

We all get biased multiple times in our lives. Biases can take many forms and they can be difficult to overcome especially when we don’t even realize that we might be biased.

In the BBST® Bug Advocacy course, Cem Kaner talks about the biasing variable in software testing and how testers’ work might be affected. Going through this lecture while I was helping with the facelift of the course, I started thinking: How many times did I get biased and maybe didn’t even realize it? Taking a look back at previous projects, I realized there were situations in which, yes, I got biased. Reflecting upon this was a useful exercise to better understand myself and how I react in various situations.

A project on which complex bugs were being underestimated

One of the projects I worked on was a content website that could be edited in the admin panel. My role was to test what end users were seeing on the website and how editors could quickly add more content to it.

The stakeholders’ main interest was in the website’s design rather than in functionality. The reason for this was that end users came across very few of the functionalities, while the complex part of the application consisted in the admin panel.

That is why the complex bugs (the interesting ones) were found in the admin panel and why most of them were rejected for reasons like:

- The editors were in-house and could be trained to use the product

- Major feature redesign will be expected sometime in the future

- Editors didn’t really need that feature, so it was better to limit their permissions

While these were understandable decisions, from a testing perspective it became frustrating at one point to keep having bugs rejected instead of being fixed. Obvious bugs, e.g. save doesn’t save, were acknowledged and fixed. However, they rejected bugs like this: in the Version History section, previous versions of articles were not showing the according previous title, but the current published one.

Soon enough, I started to think about the found bugs, asking myself if the stakeholders would be interested in fixing them or not. Slowly, I became disappointed when finding such bugs instead of feeling excited or challenged.

I started to invest more time in searching for workarounds for the found bugs than in maximizing, generalizing, or externalizing bugs. Most of the time, workarounds were preferred as being the cheaper and faster solution. And this was a common behavior on the project.

In one of the sprints, they asked me to test the display of the websites on mobile devices. I tested on multiple devices, different OSs, and different browsers, logged the found issues, retested the fixes, and finally sent the app to UAT.

A few issues were reported from their side, but one of them surprised me. On one of the pages, there was a bullet list, and the indentation of the list kept its size from the desktop version. So bullets were placed on the other half of the screen and the text was taking up a very small area of it.

The stakeholders asked me if I hadn’t seen this while I was testing. I saw the page and I saw the indentation, but I didn’t see the bug – I didn’t consider what I was seeing not being acceptable: users could read the text, the page was reachable and usable. During my testing, I hadn’t seen anything wrong with it. I was biased by the stakeholder’s approach to defer many of the bugs.

The missed bug

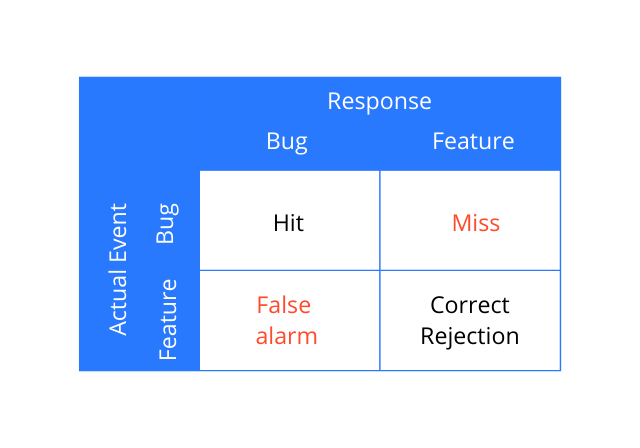

Cem calls this a miss and explains it with the Signal Detection diagram. As you can see in the diagram below:

- if testers report a bug that is actually a bug – that is what he calls a hit

- if they correctly identify a behavior as a feature – that is what he calls a correct rejection

- if a bug is interpreted as a correct behavior – that is a miss

- if a correct behavior is interpreted as a bug – then it is a false alarm

Looking at this diagram, Cem explains:

You might be more likely to say bug, or more likely to say feature. If you have a bias toward saying bug, you will have more hits, but more false alarms, fewer misses. If you have a bias away from saying bug, you’ll have more correct rejections, fewer false alarms, more misses.

BBST® Bug Advocacy, Lecture 6, slide 170

The ‘dismiss complex bugs’ attitude biased me to no longer observe the bugs for which the functionality was not affected or for which I could find workarounds. And this bias led to a miss – luckily, the miss was a small one and could be fixed before going to production.

My takeaways

In order to practice making more objective/less biased decisions, first I need to identify what my biases are. I don’t expect to identify all of them, but I think I can find patterns in the things that bias me in my testing activities. I intend to keep doing reflection exercises so that I can better recognize patterns when I’m biased, hoping that at one point I will be able to spot them before actually making a decision.

One of the BBST® Bug Advocacy Course chapters is about Credibility and Influence. Biases and how we make decisions under uncertainty will influence the team’s perception of our work and it will help to increase (or decrease) the credibility that we spread further. How do I gain the trust of my team members is my next reflection assignment!

Discussions

Share your take on the subject or leave your questions below.